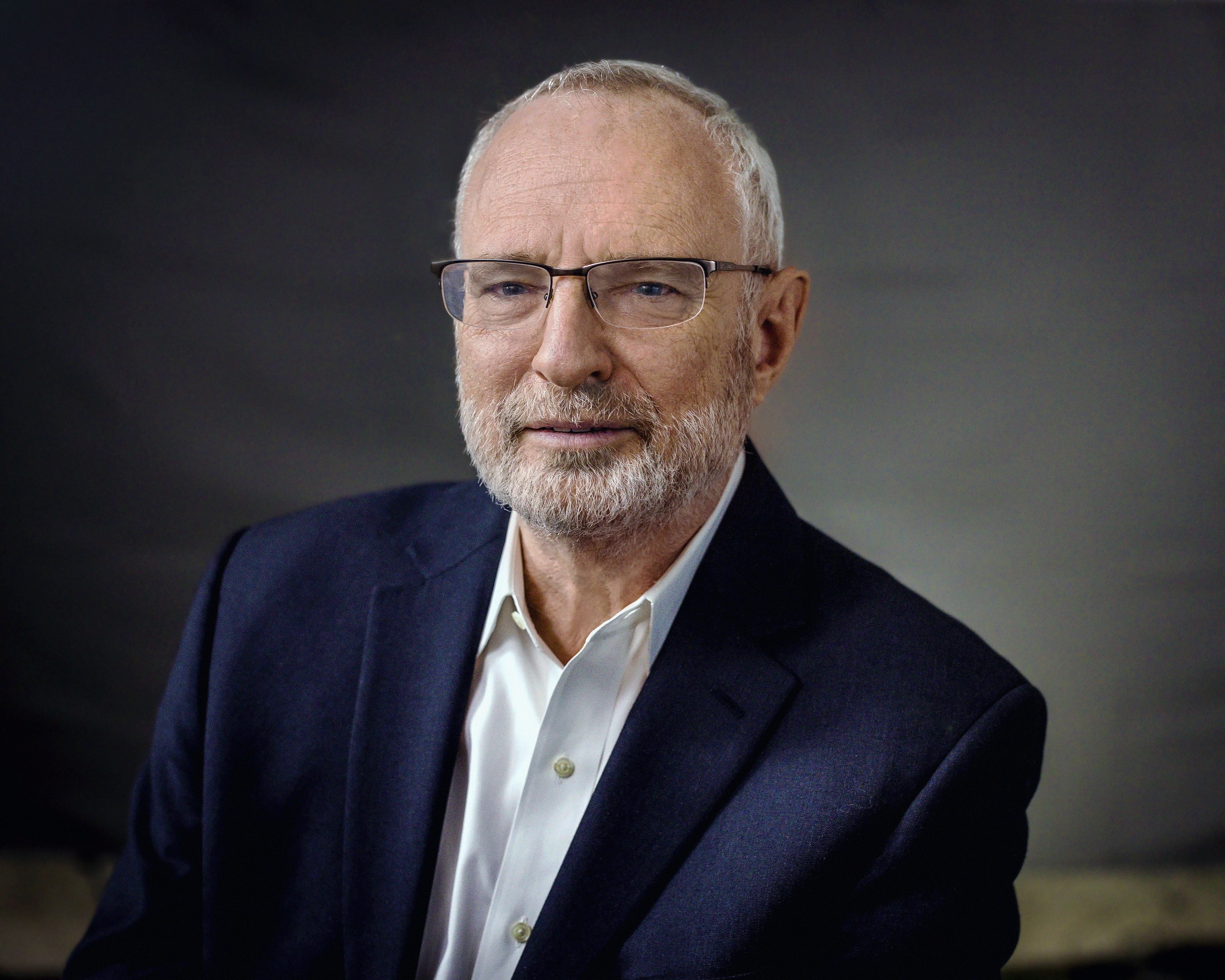

What does the Eternal require of you: Only to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with your God. This was Al Vorspan.

This giant for justice, larger than life, who lived with gusto and laughter, and strode across the landscape of American Jewish social justice for three generations pursuing a vision of justice, peace, compassion, and decency has left us. His peers as Jewish social justice heroes -- Stephen S. Wise, Louis D Brandeis, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Roland Gittlesohn, Robert Gordis, Balfour Brickner, Maurice Eisendrath, Elie Wiesel, Leibel Fein, Jane Evans -- they have all passed from the scene. Al Vorspan was the last of the Jewish social justice titans of the 20th century, who shaped Jewish life with its embrace of tikkun olam.

That the polls show social justice as one of the most common organizing principles of Jewish identity in America is in no small measure the impact of Al Vorspan. Shaping the agenda, character, and values of the institutions of the largest stream in American Jewish life, his impact was profound and lasting:

- His efforts in the ‘50s with Rabbi Gene Lipman to develop congregational social action committees institutionalized social justice at the local level;

- His widely used books on social justice written in different forms from the 1950s to the 2000s, inculcated social justice awareness and values in generations of religious school children, confirmation and high school classes, youth groups, and social action committees (I cannot convey to you what fun it was to write a book with Al);

- His pivotal role in creating the Religious Action Center – Jonah he was so proud of what you are doing at the RAC just as he was of Eric Yoffie and Rick Jacobs’ leadership of his beloved Union for Reform Judaism (URJ);

- His two decades of classes at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC-JIR) with Rabbi Jerome Davidson, enshrining those values in our seminary and developing knowledge and skills that have greatly enhanced rabbinic leadership on social justice issues;

- His speeches that inspired the movement and spread his social justice message throughout the Jewish community.

Taken together, Al Vorspan galvanized an awareness and acceptance of the inexorably interwoven nature of Jewish particularist and universalist values and concerns. He and Leibel Fein gave us the language we all use today to transform our ancient prophetic values into the very essence of social justice in North American Jewish life – and we are all in his debt for that.

These were not easy tasks or battles, but Al Vorspan was the living embodiment of what his dear friend Leibel, his comrade in arms in the battle for Jewish social justice in America, described when he said:

Yeats once wrote that “to be Irish is to know that the world will break your heart one day.” Well then, to be Jewish is to know that the world will break your heart almost every day, to know that that which you have planted in the morning may well be trampled by sundown – and, stiff-neckedly to be there the next morning and the next, and the one after that, for as long as it takes.

It is in this spirit that we hear Al’s warning in this era of this president:

The last time I felt such despair was in 1945,” he wrote, “when my ship was almost destroyed by a kamikaze plane in the Pacific, and I saw shipmates, dead and wounded, lying on the deck and my ship afire….

Ripping babies from their mothers and separating families at the border is not the America I imagined after Hitler and Hirohito.

I see democracy losing ground in America. The signs: our free press is under attack. The lie has become a weapon to shatter civility. White power nationalists have been emboldened to openly spread hatred and exclusion here and abroad….

… this is only an early round in a long fight that I know my kids and grandkids and millions of outraged Americans, jolted awake, will ultimately win. America once again will be the light to the world.

We need Al Vorspan more than ever today. So, there is an empty place in our hearts as we gather here; but, in our coming together to celebrate, in our love for Al and Al’s many diverse families -- his beloved Shirley and Chuck, Robby, Kenny, and Debby and each and every grandchild and great-grandchildren; his URJ family; his Commission on Social Action/RAC family; his Hillsdale and his Great Barrington Hevreh family; his Woodland Pond family; his extended family and his lifelong friends… All of us, his larger family – we are comforted, inspired, and ennobled being here.

I have to interject a note here to recognize two great ironies regarding the timing of Al’s death. First, he died on the same day as one of the most beloved lay leaders of the past 30 years of Reform Judaism, Judge David Davidson. Dying on the same day they were—our Jefferson and Adams. I ended my eulogy for David yesterday observing that I could envision the two of them, our own Humphrey Bogart and Claude Raines, linked by a beautiful friendship heading together down a different road to justice as they walk humbly with their God.

And then today I see The New York Times’ obit page with Al’s obituary and, alongside it, that of Don Newcombe, the African American pitcher on the Brooklyn Dodgers, whose 20-5 1955 season brought the Dodgers to their greatest triumph. You have to remember that Al was such a rabid Dodgers fan, he spent six years sitting in the bleachers at Ebbits Field after the Dodgers abandoned them for L.A., convinced they would see the errors of their ways and return. With apologies to all the Yankees fans here, Al and I used to muse on the theological implications of the ’55 World Series victory after so many times going down in the series to defeat by the Yankees. To us, it testified to the certain triumph of good over evil and the assurance that one day the Messianic age would come. Now the Times has ensured that Al and the Boys of Summer will be linked together in posterity.

Look: You who gathered here and Al Vorspan’s mourners everywhere – you should read the tributes and emails that have flooded in from across the world -- you all reflect, as well, the immense range of the passions of his heart: A proud American, a passionate liberal, a devoted Jew and an equally passionate Democrat (which in Al’s view was the same thing), a writer and consummate storyteller, a courageous and outspoken champion of the downtrodden, the persecuted, the oppressed, and a tireless advocate for good government, for oppressed Jews anywhere, for international peace and human rights, for Israeli and Palestinian peace, for equality for all without regard to race, religion, gender, ethnicity, or sexual identity – for all were created in the image of God.

And he didn’t just fight for policies, he lived his belief that the spirit for the divine was in each person. He was a great friend, and a totally kind human being.

Truly, when it came to being a mensch – Al Vorspan was the state of the art.

[All of us who have gathered here to celebrate Al’s life and to mourn his death are evidence to his outsized capacity for optimism, for causes championed, for abiding political alliances, and for deep and lasting friendships for his beloved Shirley and Al. Indeed, if Al is looking down, I suspect heaven is hearing that rollicking laughter as he delights in these songs and these tributes by the very people, the very songs, he chose. Indeed, Al and I had our version of the delicious story David Stern shared earlier about his father and Al’s commitment each to do the other’s eulogy—whoever died first. Al made a similar request for me – as source of much humor with his family over the years. When we promised each other 25 years ago, whoever died first would be eulogized by the other, he said: “Don’t worry you’ll be great – I’ll write it for you. He did – and it would have been much better than mine – but regretfully, none of us could read his handwriting.]

In his eulogy for Yetta Barshevsky Schachtman, the Nobel Laureate Saul Bellow writes, “There is something radically mysterious in the specificity of another human being which everybody somehow responds to.”

Radically mysterious specificity of a human being to which everybody somehow responds – Indeed.

That Al Vorspan lifted me up to serve as the director of the RAC, that he so generously nurtured, mentored, nudged, guided – and edited – me, was truly one of the greatest blessings of my life. For when Al Vorspan was editing and guiding you, you knew you would shine. As with so many of you, I experienced vividly the specificity of Al Vorspan to which everyone seems to respond. One example: I spent months every year of my career, traversing the country to speak at conferences, synagogues, churches, universities, and raise money for the RAC and URJ. And in those thousands of talks, over and over again, people would come up to me after the talk, would say some perfunctory nice words on the speech and then get to what they really wanted to say: “Do you know my good friend, Al Vorspan?” “Yes,” I would respond: “I do indeed -- he is my mentor, my colleague, my friend, I work with him daily. Do you know him well ?” “Well, we only met once, actually,” they often replied, “but there was something special between us; we really connected. He got me,” they would say, “ he encouraged and inspired me. Please send him my warmest regards. I’m sure he remembers me.” Al had that indefinable gift, manifested by many great politicians – and great rabbis, I would point out -- of focusing so entirely on someone speaking to him, that it would seem to them both that the rest of the world had vanished. And he really, really listened and deeply engaged and responded to what you said. And often he did remember. Indeed, dare I say -- of all the public figures I have been blessed to see in action, Bill Clinton and Al Vorspan lived this gift with more completeness than any others I have met. And if those people treasured that one encounter with Al Vorspan, how wondrously fortunate we all were to have that warmth, that caring, that support, that encouragement, that joy for so many years.

Then there was his joie de vivre – his absolute joy of life, his joke-telling, his good nature, his many kindnesses. A superb joke teller, he could regale you with stories for hours. Three qualities characterized his jokes and quips. First, he really listened to you when you told a joke. [I know other great joke tellers, who when someone else was telling a joke would just be thinking about the next one they would tell.] Al would get completely lost in your story and you knew it was a good one not by how he laughed – because he would always laugh full-heartedly at jokes and stories told by others but by whether he pulled out his scrap of paper that every day he put in his pocket to jot down quips, one liners, jokes, stories, he heard that he liked. It was a ridiculous system – scraps of paper everywhere with his scrawl that even he couldn’t always interpret (my staff would argue it was a quality that he implanted in me somehow). But, magically, the quips and jokes would appear in his books and speeches.

Another joke telling lesson he imparted: I remember one time, Rabbi Jordie Pearlson started telling us one Al and I knew, so I interrupted to tell him. Jordie paused for a moment, looking disappointed and then shifted to tell another one. Afterwards, Al put his hand on my shoulder – you know that move right – right hand on your left shoulder, the other one soon lifted to make you look at him -- and he said: just want you to know, I never tell people I have heard a joke they are telling. First, it defuses their joy. Second, if you really listen carefully you may hear something in their telling that is better than the way you tell it. I have followed that advice from that day on, including when I would hear Al’s jokes for the 20th time. Shirley was equally accepting, reminding Al when he would get off-track on a joke. She knew some of them better than he did.

And of course, all of you who have heard Al tell a joke know what I will say next: No one, no one, laughed harder at Al’s jokes than Al Vorspan did. He would tell you his story; you would burst out laughing just as the laughter started to rumble up in Al’s chest until he would be convulsed in laughter, arms crossed, bent over. his laughter and joy became infectious. So, first you would laugh at his joke, then you would laugh at his laughing at his joke. He did it every time and it was a thing of wonder to watch.

But it was his social justice passions that marked his impact on Jewish life in America. He was so often the face the Jewish community at crucial times on urgent causes. And he drove the Reform Movement in its engagement on these issues and often the larger Jewish community. Consider:

- His lead role on the movement’s civil rights efforts, just as he had helped integrate the crews’ responsibilities on his Navy ship, and his role as the only non-rabbi on the famous protests and imprisonment in St. Augustine with his contributions to the famous letter Eugene Borowitz -- with Al’s help -- crafted.

- His lead role in opposing the war in Vietnam, his work with Eisendrath in developing the strategy , the tactics, the messaging, of their successful effort to bring the URJ to oppose the war in Vietnam at its 1965 Biennial -- years before any other major Jewish organization opposed. Some of our largest congregations withdrew from the Union for a few years but to Eisendrath and Al, it was the right thing to do and they stood their ground, playing a prominent Jewish role in anti-war efforts. It took another four years for others to join and even then…. Consider his famous speech to the 1970 NJCRAC – now called JCPA -- conference, in which, with eloquent gentleness, Al chastised the community relations field he loved, for its failures on this issue:

Does the war in Vietnam really have no bearing on civil liberties and due process and national priorities or the solution of domestic challenges. Will we be the last body in America to face this issue? There is more dissent on Vietnam in the U.S. Army in Vietnam then in NJCRAC. The ACLU regards the draft itself as unconstitutional; what do we think, we who have seen the lives of our own children racked and distorted by the agonies and anguish of conscience over the draft and the war? We have failed most of our youth and they, correctly, pay us no mind whatsoever.

But they paid attention to Al. Indeed, for decades, Al’s rousing speeches at NFTY conferences helped ensure that the flame of justice would burn brightly in generation after generation of our youth.

- His out-front leadership on the Soviet Jewry issue. With the late Betty Golumb, he kept us deeply involved in the NCSJ, and spoke frequently at rallies for this oppressed and persecuted Jewish community.

- He was a champion of the Great Society programs and spoke over and over for the rights of the poor, the hungry, the homeless, the disenfranchised, the immigrant, the children, the elderly.

- He was a lead Jewish critic of apartheid and together, he and I, once again with Rabbi Roland Gittlesohn at our side, pushed the movement to become the first national Jewish organization to support sanctions against South Africa.

- And he was a lifelong Zionist, who -- growing up in Minnesota among, as he loved to quip, the “frozen chosen” -- as a teen created his own Zionist youth group the Young Judean Trailblazers. He was a champion for Israel, a true ohev Yisrael, a lover of Israel, even when it became necessary to speak out as a sharp critic of Israeli policy. Even in that 1970 NJCRAC speech, he challenged them:

- “Are we automatic defenders of all Israeli policies as if they were handed down from Sinai? How is it that debate and dissent rage in Israel itself but are never reflected in the organized Jewish community which is asked to interpret and defend these policies? …. Are dissent and diversity mere ornaments for program plans or are they living principles to guide our relations with our fellow Jews as well.”

- And he remained constant in these views. From this 1970 speech to his famous 1988 New York Times Magazine article challenging the conscience of the Jewish community on Israel, until the day he died. If the prescience of that NYT article may have faded from our communal consciousness, the magnificent NYTimes obit today will make it evident again to the world. The Times quotes Al, writing:

“Whether we accept it or not,” he wrote, “every night’s television news confirms it: Israelis now seem the oppressors, Palestinians the victims.” When criticized by more tepid Jewish leaders, the Times noted: “Mr. Vorspan responded to the backlash with characteristic humor: ‘Behold the turtle. It only makes progress when it sticks out its neck.’”

Daniel Sokatch, the head of the New Israel Fund, said about Leibel Fein when he died, words that equally apply to Al, “It makes me particularly sad that he died while the Israel he loved so much was in such turmoil and darkness. But…we all stand on his shoulders.” Indeed, we do stand on Al’s shoulders. And he never, never despaired that one day the Israel of his dream, at peace with a Palestinian State next door – an Israel, democratic, Jewish and progressive – a true or l’goyim, a light to the nations, would be realized.

The list of issues Al led on are legion and too many to recount. But his was the shofar call, the call to arms for all Jews of conscience.

And, boy, could Al Vorspan preach and speak – inspiring talks spiced with his jokes and his favorite stories.

I have often held and still do, that Al Vorspan was the most eloquent, inspiring, compelling spokesperson for Jewish social justice of our lifetime. And here, I mean he surpassed Eisendrath, Schindler, Yoffie, and Jacobs, Leibel Fein, Ruth Messinger – each master social justice speakers in their own right. Only, with a radically different and unique style, was Elie Wiesel his equal. No Biennial convention was complete without a Vorspan hilarious electrifying, mobilizing message.

So too, his immense skills as a writer. Al Vorspan’s first draft was better than most of our tenth. He would selflessly contribute great rhetoric for you to use without attribution. His speeches were riveting; they engaged you, made you think, challenged your assessment of your moral actions.

[Time allows only one more example of the power of his rhetoric. I could have taken something from any one of his speeches I have in my files or you could open any of his many books blindfolded and hit upon eloquent powerful passages. This example:

Judaism is a way of life—sensitive, compassionated, ethical. And that is why Judaism is a shofar call to action and not passivity, social change and not resignation, passion and not acquiescence in evil. We are enjoined by our faith to take this world into our hands, as co-partners with God, and to place it upon the anvil of life and beat it into better shape.

This Jewish value stance did not die 3,000 years ago. It is alive and vital if we apply it to our times. America is in desperate search for values to live by, and we Jews have something to contribute not by dissolving into the American melting pot but by being Jewish—by being ourselves—by being a light, a blessing, a reproach to injustice, a goad to conscience, a catalyst for progress, nudniks for justice, a distinctive voice audible and proud and clear speaking above the raucous din of American life. We have our own unique value stance, tested and refined in the crucible of history, and it is this that we can contribute to a stumbling America. This is the meaning of American pluralism. That is our role. If we cannot achieve in this free and blessed land, we can achieve it nowhere. But the ultimate test will be fashioned not in negative terms—not in fighting anti-Semitism, nor giving money to the UJA for the constant emergencies of Israel, or defending our good name or huddling together for warmth against the goyim—but in grounding these values in the religious tradition they derive from, releasing the ethical Judaism into our lives and the life of this nation.

But family was always most important to Al. He loved his children and grandchildren. He was so proud of them, so supportive of them. To hold court with them all in their Hillsdale home, their Shangri-La, was perhaps the single greatest joy of their lives. I never saw Al so much at peace, Shirley so joyfully happy as when he was in that place with some combination of his family.

That sense of holding court with his family, also marked the end of Al’s life. He went out on his terms. He contracted pneumonia and did not respond to the oral antibiotics. When faced with the prospect of intravenous IVs in a prolonged stay in the hospital, Al chose to stay home. In the face of Al’s insistence he would make it to his 95th birthday three days hence, the doctor truly wasn’t sure. Al could barely talk, wouldn’t eat or drink much at all. We sent word to close friends to give their birthday greetings in emails early. They flooded in and were read to Al and—lo and behold, on his birthday surrounded by his children and many grandchildren, Al rallied. I joined them the next day and for those two days Al held court, telling jokes, eating popsicles, drinking juice, resting for a bit and then his voice would ring out: “Get everyone in here; I have some more stories to tell.” Hours each day he fielded calls, accepted birthday wishes, told stories and individually said goodbye to his loved ones the way he wanted. [I told him often that I was confident in stating that Lincoln would have been proud to have shared a birthday with Al Vorspan.]

Several times he told the Hasidic story of Rabbi Zusya who one day joined his followers deeply distraught. “Zusya,” they asked, “what is troubling you?” Zusya responded, “I had a vision in which I learned that when I go to heaven, I will be asked a question. His followers, look puzzled. “Zusya. You are scholarly and humble. You have helped so many of us. What question about your life could be so terrifying?” Zusya explained, “I have learned that the angels will not ask me ‘Why weren’t you a Moses who led your people out of slavery?’ And they will not ask me, ‘Zusya, why weren’t you a Joshua who led your people into the Promised Land?’ They will ask me, ‘Zusya, why weren’t you Zusya?’”

Watching him, surrounded by loved ones, I could not help but think of Jacob surrounded by his sons (albeit Al’s message was a bit kinder than Jacob’s blessing of his children). It was simply wonderful to watch. And then it passed and two days later he passed.

[And those children and grandchildren were so magnificently kind, supportive, and lovingly caring for Shirley and Al. They couldn’t have done more for their parents and grandparents in those final years, weeks, and days.] Al’s love affair with Shirley lasting over seven decades was something special. No one could control Al the way Shirley could; not one was more supportive of Al than Shirley was. I will repeat only one story from my eulogy for Shirley. Al had been a great champion for Soviet Jewry from the very beginning of the campaign. Al, Shirley, Mary Travers and I traveled to visit Soviet Jews in the mid-80s. Al and I gave speeches; Mary sang as I played the guitar; and Shirley engaged in intense one-on-one conversations. Our visit brought comfort and hope to those with whom we met. On one intense day, we finally took our only few hours of sight-seeing and went to the great summer palace in St. Petersburg and stood alone in the magnificent elegant opulence of the Grand Ballroom. Just around one of their anniversaries, I turned to Al and Shirley and proposed: how about if we do a celebratory remarriage here in this spot. And so surrounded by some of the world’s most magnificent art and architecture, to the lilting voice of Mary Travers singing “Dodi li,” Shirley and Al celebrated this second wedding. No one else in the world can claim that experience, but then again, Al and Shirley were one of the most remarkably unique couples that many of us have ever met.

Many of you know that Al’s idol growing up was his university professor, his governor, his senator Hubert Horatio Humphrey. Humphrey’s message that the moral test of any nation is what it did for those in the beginning of life, those in the end of life, those in the shadows of life – became the hallmark of Al’s political values.

Humphrey was known as the “Happy Warrior.” Mark Pelavin, a successor of Al’s as director of the Commission on Social Action, pointed out to me the other day that the term comes from a poem by William Wordsworth.

Tell me that Wordsworth, had he known him, would not have Al Vorspan in mind when he wrote:

Who is the happy Warrior?

Who is he That every man in arms should wish to be?

—It is the generous Spirit, who, when brought

Among the tasks of real life, hath wrought

Upon the plan that pleased his boyish thought:

Whose high endeavors are an inward light

That makes the path before him always bright;

Who, with a natural instinct to discern

What knowledge can perform, is diligent to learn;

Abides by this resolve, and stops not there,

But makes his moral being his prime care;

A generous spirit? Absolutely. High endeavors? They defined his career. An inward light, a moral being his prime care? Unmistakably so. Diligent to learn? Until his very last days.

Al can no longer carry on the fight. But it doesn’t mean he can’t pull off an upset. We can fight now, as Al did, for the widow and the orphan, the disenfranchised, the unemployed and underemployed. We can stand up for the migrants and the immigrants, the children and the seniors. We can put those at the margins of society at the heart of our efforts. And if we do, then Al will achieve his greatest victory: He will beat even death.

Indeed, in the Gemara in brachot we read “The righteous are considered alive after they leave this world.” Why? I believe it is because the legacy of their good deeds lives on and on and inspires others to do good.

George Bernard Shaw once wrote in his play “Man and Superman”:

I am of the opinion that my life belongs to the community, and as long as I live, it is my privilege to do for it whatever I can. I want to be thoroughly used up when I die, for the harder I work, the more I Live. Life is no “brief candle” to me. It is a sort of splendid torch which I have got hold of for a moment, and I want to make it burn as brightly as possible before handing it on to the future generations.

Al Vorspan you are our happy warrior. Because we followed you into battle so many times these past 60 years, let us never forget, despite the enormous battles for justice left because of what you and we did together, there are two hundred million minorities and women in America who today enjoy rights and opportunities their grandparents could have only dreamed of. Billions have been lifted out of poverty world-wide and human rights, as under attack as they are, are internationally recognized values and goals that barely existed when Al was born.

You are our tzadik who lives on after death, whose good deeds in turn will inspire still more.

You are our torchbearer for justice. You have placed that torch in our hands and we will keep that flame burning brightly so that, one day, that world of justice and peace and equality of which you dreamed and for which you fought so tirelessly will be made real for all God’s children. In so doing, we will ensure that truly your memory will ever be for a blessing.

Keyn yehi ratzon – may it be God’s will.

For more about Al, his life, and his commitment to social justice, read "Remembering Al Vorspan, z"l: The Prophet Who Loved to Laugh."

Have something to say about this post? Join the conversation in The Tent, the social network for congregational leaders of the Reform Movement. You can also tweet us or tell us how you feel on Facebook.

Related Posts

Passover 2024: The Three Central Messages of Pesach

Modern-Day Plagues of Injustice and Inequality