By Cantor Wally Schachet-Briskin

The music and the style of song leading as it has been popularized among Reform youth has moved the Jewish world. Music in NFTY and Reform camps, which began in 1951 in Wisconsin, seems to have been defined by the era in which it was sung, affected greatly by world events, politics, and technology. Camps were where adolescents gathered to form communities: mini-societies. Singing begins as a family activity, and this “family” atmosphere is created in the camp community.

Repertoire at the West Coast’s Camp Saratoga, which was established in 1951 (and later became UAHC Camp Swig and then URJ Camp Newman), was chosen from American folk songs, some Hebrew, a little Yiddish, and hymns from the old Union Songster. The first songleader at Swig in 1955 was Cantor William Sharlin, an accomplished composer in his mid-30s, who had been to the Union Institute in Wisconsin the previous few summers. He was the first staff member with a professional music background, and was hired to take singing to the next level. Since Cantor Sharlin had come from the only other Union Institute, the repertoire of both was virtually the same. The songbook that Camp Saratoga used was from the Jewish Agency from the 1940s. No set curriculum was instituted, although most of the song sessions helped prepare for Shabbat. By the second summer Saratoga was in session, the natural phenomenon of “tradition” had come into play: what was sung the first summer was “how we’ve always done it.” The kavanah [spontaneity] of the first campers had become the keva [fixed] of the second summer. This circumstance has been both a blessing and a curse to the camping movement ever since.

Campers would sing after every meal, and the most important curriculum component the songleader had to worry about was striking an even balance between two or three English folk and protest songs, (e.g., “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine,” “She’ll Be Comin’ ‘Round the Mountain,” “Follow the Drinkin’ Gourd”) and two or three Hebrew songs from liturgy and the modern State of Israel, (e.g., “Hava Netzei B’Machol,” “Atzei Zeitim Omdim,” “Sim Shalom”). Cantor Sharlin said the songs were written on large pieces of butcher paper and posted around the chadar ochel (dining hall) during the week, and by the time they were taken down for Shabbat, the campers had memorized the songs.

For teens in a camp away from parents, singing became a way of expressing emotions, sentiments, and solidarity. The songs that campers were bonding over were songs in English with messages they could stand behind, as well as the songs of the Jewish people. This deepened their connection to the music of the Jews — and to the Jews who were singing it.

Some of the Hebrew songs that found their place in the Reform camps were penned by Orthodox Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, whose first recorded album was produced in 1959. Several of his compositions that were brought to camp, such as “Am Yisrael Chai,” “Od Yishama,” and “Esa Einai” are sung among Reform youth to this day.

While much of the early repertoire — Yiddish songs, English brotherhood songs, and hymns — have disappeared, the core of NFTY music, from its roots in the 1940s and ‘50s, remains spirited, communal singing, which speaks to Jewish youth on a deep level.

Cantor Wally Schachet-Briskin serves as Cantor at Ohef Sholom Temple in Norfolk, VA. He was a camper, Head Songleader and Faculty Member at URJ Camp Swig-Newman. He was ordained in 1996 from HUC-JIR’s Debbie Friedman School of Sacred Music, where his Masters Project covered the “Music of Reform Youth.”

We are grateful to Women of Reform Judaism who have supported NFTY for 75 years and continue their generosity as Inaugural Donors to the Campaign for Youth Engagement.

Related Posts

Image

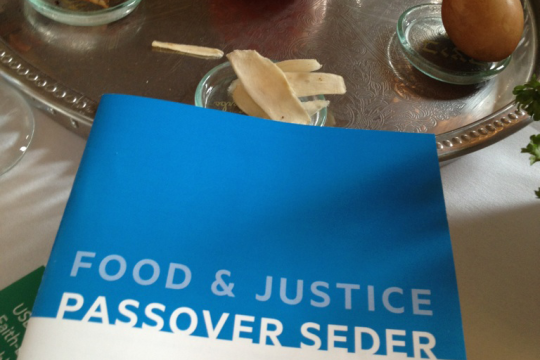

Passover 2024: The Three Central Messages of Pesach

The Exodus story is the master narrative of the Jewish people. As most of us know, it tells the story of the Hebrew slaves in Egypt and the rise of Moses as their liberator. It reminds us that in 2024, the universality of Passover's three-part message again reverberates through the generations: freedom, love, and justice.

Image

Modern-Day Plagues of Injustice and Inequality

On Passover, we recount the Ten Plagues that were inflicted upon the Egyptian people. Here are some of the "plagues" and injustices that afflict our present-day society -- and actions you can take.

Image

Setting Your Leaders Up For Success

It's board nomination season again! Time to compile lists, get recommendations, and start calling the future leaders of your congregation. The URJ has resources, advice, and initiatives to set you and your board up for success.