Editor's Note: The following d’var Torah was given by Rabbi Rick Jacobs during Shabbat morning worship at the Union for Reform Judaism Biennial 2015 convention on November 7, 2015.

Falling in Love

Did someone offer a eulogy at Sarah’s burial?

The Torah tells us that she lived to be 127, but the text focuses on the intricate details of her burial arrangements. It has fallen to millennia of commentators to craft a fitting tribute to the first Jewish woman.

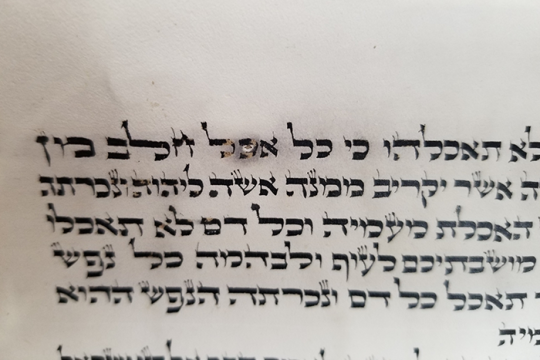

The 11th-century master commentator known as Rashi offers us a frame for Sarah’s eulogy:

Shanei Chayei Sarah kulan shaveen l'tovah – the years of her life were all equally good.

Really? How could this be?

All lives have moments of heartbreak and disappointment, Sarah’s more than most. How could it be that the years of her life were all good?

Commentators have an answer. Sarah, they tell us, could always find the good in all situations – and in all people. This perspective allowed her to experience her years as: כלן שוין לטובה – all good.

Our mother Sarah was a spiritual master of the highest order, a full partner with Abraham in launching our Jewish journey through history, a woman you could not help but love, and could only hope to emulate.

We don’t know who eulogized her. We don’t know who, if anyone, stood with Abraham and Isaac laying her to rest in the Cave of Machpela.

But we do know this: None of them was Jewish. Still, as they reflected on the nobility, depth, and resilience of her long life, I can imagine that many of them might have fallen in love, not just with her, but with Judaism itself.

And what of Abraham? The father of the Jewish people is left with a bundle of promises from the Holy One, a good amount of material wealth, and not much else. Worse, he knows that the Jewish journey will end abruptly unless a suitable partner can be found for his grieving son, Isaac. And there are no Jewish women to be found.

In this moment, the founder of our spiritual path is alone. Seeking to purchase a burial plot, he identifies himself to Ephron the Hittite, saying: “ גֵּר־וְתוֹשָׁב אָנֹכִי עִמָּכֶם— here I’m an outsider, a stranger, not one of you.” (Gn 23:4)

No one is immune from being a ger, an outsider, not even Avraham avinu. In fact, we seem to need the imprint of that pain and sensitivity in order to live our tradition. That journey – from the outside in – can be traced in the Hebrew from ger to giyur: from stranger to one who chooses Judaism. Abraham and Sarah themselves were not born into Judaism; they were the first to make that journey, and then spent their days sharing their sacred call with others.

In his grief, Abraham empowers his trusted servant Eliezer to find the “right one” for Isaac. But there’s a condition: He insists that Eliezer “not take a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites among whom I dwell, but will go to the land of my birth and get a wife there for my son Isaac.” (Gn 24:3-4)

That stern instruction has made its way down through the generations. When I was nine years old, my Eastern European immigrant grandma Sophie took me aside and told me that she loved me with all her heart – but that if I married someone who wasn’t Jewish, I’d be dead to her and she’d say Kaddish for me. I love you too, Grandma!

I get it. My grandmother isn’t the only Jew for whom the notion of intermarriage awakens fear and danger, calling into question the divine promise made to Abraham and Sarah and all the subsequent generations: V’heyeh bracha – you shall be a blessing.

Since our Biennial in San Diego, a group of thoughtful Jewish communal leaders has said that, by accepting the reality of intermarriage instead of preaching that Jews should only marry Jews, I’m leading our people off a cliff.

To be clear: Few things warm my heart more than watching Jews fall in love with Jews. That’s why the URJ is leading a variety of communal strategies designed to bring young Jews together in the hopes that they’ll form meaningful social connections. Youth engagement, Birthright, and connecting families with young children all help our synagogues bring people in from the margins. We are deeply committed to strengthening Jewish life, and that’s a big part of the work we’re doing under the banner of audacious hospitality that many of you have heard me speak about so much.

But decades of railing against intermarriage and castigating Jews who fall in love with those from different backgrounds have only closed doors and hearts. And as much as I love watching Jews fall in love with each other, our focus must be on helping more and more of our people to fall in love with Judaism.

It shouldn’t be that hard – we’re very lovable! We have so much to offer – and, on Thursday night, I talked about how our relevant and inspiring contemporary faith makes us a real catch. But if we want people to fall in love with us, we have to be willing to meet them where they are.

Go back to Abraham. Does he really prohibit Eliezer from entering Isaac into an intermarriage? Isaac Abravanel, a 15th-century Portuguese commentator, puzzles over the instruction, asking, “Why did Abraham command Eliezer not to take a wife from the Canaanites? Was it because they were idol worshippers? Surely the inhabitants of Babylon – Aram-Naharaim – were no better.”

Indeed, Eliezer’s mission wasn’t to find a Jewish wife for Isaac – there was no such woman on the planet. It was to find the “right one” – one who would be open to the same journey, from the outside in, that Abraham and Sarah had taken, one who would fall in love – not just with Isaac, but with Judaism as well.

Welcoming Those on the Periphery

I spoke on Thursday night about tikkun olam as a gateway to a Jewish life. Audacious hospitality is how we swing that gate wide open to welcome in those who are on the margins. But it isn’t just about being warm and friendly. It’s a transformational Jewish practice, one that stretches us into the people and communities we were meant to be.

We aren’t erasing boundaries; we’re removing barriers.

We aren’t diluting Judaism; we’re sharing it.

So who’s standing out there on the outskirts of Jewish life?

Surely, the largest number are those who are not Jewish but nonetheless are part of a Jewish family. That’s why, a few years back, the URJ blazed a new trail by opening our synagogues to interfaith couples. Since then, the numbers have grown larger, but our strategies haven’t kept pace.

Look further. What about the 10 to 20 percent of our community members who are Jews of color? What about LGBTQ individuals and couples, who were shunned in most congregations back in the 1970s but who find a more welcoming home today. What about people with disabilities? The contributions of them all makes us more whole.

What about those who were once a part of Jewish life but now feel alienated or simply disinterested? What about the young adults who don’t see themselves participating in congregational life, now and perhaps not ever? What about those of us who are members of our congregations but still find ourselves on the periphery?

And what about those of us who are here only because someone or something opened the door and welcomed us in?

Eliezer makes his way to Aram-Naharaim, to the city of Nahor, well beyond the land of Canaan. He prays that God will help make his errand fruitful, asking that the woman who is to marry his master’s son appear and offer him and his camels water to drink. And that’s exactly what happens.

Rebekah may well be the most gorgeous woman in Nahor, but if she is, the Torah doesn’t seem to think that’s important for us to know. What we do know is that Rebekah is generous, gracious, and inspiringly – dare I say audaciously? – hospitable. Rebekkah’s care for a total stranger and his entourage at the well is described in the text as an act of chesed v’emet. Ibn Ezra explains: Chesed, kindness denotes an intention to do something that is not obligated, while emet, truth, means to give permanence to the kindness. How do you say audacious hospitality in Hebrew? Chesed v’emet.

Our challenge is to act like Rebekah toward the strangers on the outskirts of our own community.

On Thursday night, we discussed tikkun olam, perhaps the greatest gateway of all into our Jewish world. But not everyone is peering curiously through the same doorway. My way in may be through open-minded and probing study of sacred texts. Yours may be in soul-searing spiritual prayer. Someone else’s may be by caring for those struggling with illness or comforting those whose lives are broken by economic or emotional hardship.

Practicing audacious hospitality – working hard to invite people in through whatever door they feel is most welcoming – doesn’t just lead to larger congregations. It leads to a more vibrant, more diverse, and more engaged community. It makes us more thoughtful Jews.

* * *

Someone once asked if we have interfaith couples in our congregation, to which I answered, “That’s all we have.” Look around a congregation, and you’ll see a modern orthodox mother married to someone from an Episcopal background. Or a conservative Jew married to someone from a classical Reform background. Or a former Catholic who fell in love with someone from a secular Yiddish background. Or an atheist married to a proud, believing Reform Jew.

That’s one of the reasons our Movement has grown – and it’s not just that we’re the easiest choice for people from diverse backgrounds. Building a congregation with a deep commitment to spiritual and religious diversity is a potentially redemptive experience.

* * *

Think about how much of our lives we spend around those who look like us, dress like us, earn like us, vote like us. There are very few places in this world where we are forced to live serious pluralism of the kind that forces us into conversations and relationships. But our congregations should be among them, because the world our faith compels us to repair is dizzyingly diverse.

Is our work combating racism an issue of audacious hospitality or tikkun olam? Clearly, it is both – and it’s also about strengthening congregations. Indeed, it’s no coincidence that this holy work in particular brings together all of our URJ’s strategic priorities.

The imperative to repair the brokenness in our world starts at home, as we strive to repair those broken places within each of us. And ensuring that our congregations and communities are naturally diverse and welcoming makes them uniquely powerful places to appreciate and cherish the fact that, although we are all different, God made each of us the same – in our innermost core.

I love to pray in a community where women can wear tallitot and kippot next to men with neither, alongside elders with kippot but no tallitot. I long for the day when a young woman from an African-American and Jewish family walks into shul and no one assumes she’s lost. I want to see a strong opponent of the Iran deal wish a heartfelt yasher koach to an ardent supporter of the deal after her aliyah to the Torah.

Audacious hospitality doesn’t assume that the truth is held inside our congregations and doled out to those we let in, but rather that each person brings in a piece of truth, enriching us all.

Our Many Communities

A congregation that’s built with audacious hospitality is a foretaste of the world as it could be. But for us, as for Rebekah, audacious hospitality doesn’t take place only in the home or in the synagogue. It must be practiced everywhere.

Congregations are the most inspiring and adaptable sacred Jewish communities the Jewish people has ever created. But they are not our only sacred communities.

Each of our 15 summer camps is a remarkable community, and so is each of our many NFTY communities throughout North America, and so is each of our day schools, and so is a Birthright bus and a Mitzvah Corp cohort in Costa Rica, and a Moishe House, and a Hillel House.

If we strengthen only our congregations, we will not be strong. Thursday night, we saw how dance can serve as a metaphor for our movement. This morning, let’s try music. If you want individuals to develop a love of music, it’s not enough to build and maintain concert halls. If you want more people to acquire a love for song, you need to cultivate a wide range of experiences that, together, ignite passion for music: Spotify, music camps, after-school lessons – you get the idea.

That’s why the URJ is working to connect camps to congregations to NFTY, and to strengthen the network of Reform Jewish life with a growing number of onramps. In an effort to strengthen our congregations, we partner with federations, foundations, BBYO, JFN, Hillel and other communal institutions to shape a web of connectedness that can more deeply engage more and more of us and our youth in Jewish life.

Moments of Opportunity

Our theory of change also reflects that, when it comes to the journey from the outside in, people are more apt to take that first step at some moments than at others.

And, yes, falling in love is one of those moments, when you dream with the person your heart has chosen, imagining a new life together. Rabbis and cantors have a unique ability to help couples incorporate Jewish rituals, symbols, and practices in their lives. I challenge us to find a more effective way for our clergy to meet young couples where they are and work with them to shape a holy ritual that fits who they are than at that moment when they are imagining their new life together. As these couples plan their ceremonies – and their lives – we need not only to be ready to help, but also easy to find.

The 3.5 million people who have come looking for us at ReformJudaism.org have found resources to infuse their lives with Jewish meaning, from sacred texts and guides to holy days, and from God to Israel. They also can find each of our nearly 900 congregations. Why can’t they also find our fabulous clergy?

Audacious hospitality can begin with virtual connections. Through this portal, seekers can find all of you and more.

Another “step-taking” moment comes when couples bring children into their families, opening themselves up to “trying on” practices that may not previously have been a part the couple’s life, including bedtime rituals and Shabbat table practices. Indeed, engaging families with young children is a key way to help create anchors of joy and gratitude.

With help from our partners at PJ Library and by working with our Communities of Practice, we are building communities of families with young children -- many if not most of which are interfaith. Many include Jews of color. Although not all of those who fall in love with the excellence of our programs and the spiritual and ethical anchors of Judaism will become members, many will. And, those who don’t may find other pathways to Jewish commitment and responsibility.

And, yes, death is another of those lifecycle moments that opens us to deeper connections.

Our tradition teaches that when we care for the dead, as Abraham does at the opening of the parashah, it is described as chesed shel emet, an act of pure kindness because the generous deed can never be repaid.

When my dad died this past summer, my family and I were held in the loving embrace of our communities. We could not have received what we received in a fee for service community. Imagine if I had to call the fee for service Jewish community: “Yeah, my dad died, can you send over to our home nine loving people who know and care deeply for my family to make a minyan and bring us comfort? Oh, and by the way, how much do you charge for these folks? Uh huh, and is that per night or is there a deal for the whole shiva?”

Now, I understand the dilemma for synagogue clergy. If we’re busy caring for those who are not yet members, how can we have time to care for those who’ve made the membership commitment?

I asked that question of Rabbi Harold Loss as he picked me up on the way back from officiating at the funeral of a non-member. His Temple Israel in West Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, is our largest congregation. “Harold,” I asked, “how in the world do you have time to care for a non-member when you have more than 3,000 households?”

His answer expressed a deliberate strategy to move people from the outside in, through authentic and unstinting doses of audacious hospitality. He understands that a time of loss can be a gateway in, and that those on the margins who experience our loving care and audacious hospitality in that moment are more likely to find their way into the heart of our community.

What we learn from the power of acts of chesed, such as audacious hospitality, is that you can’t measure the impact in narrow terms alone. We practice audacious hospitality because it is a holy act that sometimes will lead people to become “members” of one of our congregations. But even if they don’t join immediately, they will be affirmed and encouraged to come closer in Jewish life. And one day down the road, they may choose to connect more deeply with us.

Conclusion

It takes time to increase our membership this way. This isn’t speed-dating with a ketubah in our hands. We’re not spending 30 seconds selling ourselves to total strangers and then popping the question. I believe it was the great commentator Diana Ross who cautioned us: You can’t hurry love.

But it works. Our outreach and inclusion work already had had a dramatic impact on Jewish life. In Boston, the partnership among Combined Jewish Philanthropies, congregations, camps, and other institutions has doubled the number of interfaith families raising Jewish children.

Meanwhile, Len Saxe of Brandeis University just released new research that reveals that millennial children of intermarriage are more likely than older counterparts to have a Jewish religious background.

In plain terms, the study proves that interfaith outreach works. When we welcome millennial children of interfaith families into our many communities, they fall in love. Thanks to our outreach efforts, these young people are more likely to have been exposed to Jewish education, and to have celebrated a bar or bat mitzvah than older peers. As adults, they are more likely than older counterparts to remain in our community.

Moving forward, we must take this outreach to another level completely. With a coherent and comprehensive practice of audacious hospitality, we will bring a deep, compelling, and inclusive Judaism to an ever-increasing community of people. In addition to practicing audacious hospitality in our own movement, we need to make sure that our local federations and other communal partners understand this extraordinary opportunity. We are in the best position to advocate for this winning strategy across the spectrum of Jewish life.

When we practice chesed v’emet – deeds of loving kindness – and offer the substance and nourishment of Reform Judaism…when we embody the compelling values of our tradition, sharing its wisdom, power, and beauty...people fall in love.

And when we call up the various aliyot for our reading of Chayei Sarah, we’ll see that inclusion has not led to diminishment. On the contrary, we’ve enlarged our leadership and our ranks with many who wouldn’t be here today were it not for the lowered barriers and the deep substance of our Torah.

In 1920 the German Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig established an institute in Berlin called the Lehrhaus. Its purpose was to open intellectual and spiritual doorways so the Jews of Germany could find their way to the riches of Judaism. Rosenzweig gave an address at the opening in which he underscored our charge:

All of us to whom Judaism, to whom being a Jew, has again become the pivot of our lives—and I know that in saying this here I am not speaking for myself alone—we all know that in being Jews we must not give up anything, not renounce anything, but lead everything back to Judaism. From the periphery back to the center; from the outside, in. (On Jewish Learning, ed. Nahum Glatzer, p. 98)

But the truth is that neither the center nor the periphery is static. That’s the beauty and mystery of audacious hospitality.

We’re all on a journey from the outside in and simultaneously from the inside out. Audacious hospitality can help each of us, no matter our background, find nourishment with the living embers of Torah.

As chronicled by the Mishnah, the great sage Hillel reframed the leadership of Aaron the high priest. With inspired clarity, Hillel charges us all to “Be of the disciples of Aaron, loving peace and pursuing peace, loving your fellow creatures and bringing them close to the Torah.”

Ohev et habriot u’mekorvan laTorah: Love all people and bring them close to Torah. It doesn’t say love all Jews and bring them close to Torah but all people.

Is it possible that at one time we practiced audacious hospitality with all of God’s children? Surely, we must do so now – because those on the margins today may be leading us tomorrow, and our movement will be all the richer for it.

Rebekkah, Hillel, and Aaron, as well as the many groundbreaking leaders of our movement over the years all have given us the tools we need to strengthen our congregations and our other sacred communities, inspiring more and more people to fall in love with Judaism.

What are we waiting for?

Related Posts

For Small Congregations: Adult Learning and Purim Celebration

The Five Commandments of Basic Torah Maintenance